How tourism and a national park pushed the indigenous people of Ko Lipe into a corner

A look into the Urak Lawoi, the original inhabitants of the Butang Archipelago.

More than a century ago, boat-loving people turned a tropical archipelago into their home and lived off the sea and jungle. After a while, outsiders pushed them aside in a burst of state-sanctioned conservation and profit-driven tourism, two things that are more related than you might think. This is the story of the Urak Lawoi people of the Butang (or Adang) archipelago in Thailand’s Lower Andaman Sea.

I’ll preface this fascinating story by pointing out that many of the archipelago’s islands have two commonly used names — one from the old Malayo-Polynesian dialect of the Urak Lawoi natives and the other coined by Thai people who took hold of these islands more recently. These baseline disagreements hint at the friction that surrounds so much of the archipelago’s history.

Urak Lawoi kids head home to their village on Ko Lipe at dusk in March 2017.

For example, the Urak Lawoi call the archipelago’s fifth largest island Pulau Bitsi (“Iron Island”) while Thais refer to it as Ko Lek or “Small Island.” The commonly used name for the third largest island, Ko Tong, is a Thai rendering of the original Urak Lawoi name, Pulau Betak or “Bamboo Island.” As for the fourth largest island, the name Ko Lipe comes from the Urak Lawoi nipih, meaning “flat.”

If you’ve ever wondered why Ko Lipe has a Pattaya Beach, it’s not because this popular island has a connection to that heavily touristed city on the Upper Gulf. In fact, a “beach” is a patay in Urak Lawoi, and they call this specific beach Patay Daya. You can see how Thai tongues fused those words into “Pattaya.”

Like most of the maps handed out to tourists on Ko Lipe, this one only includes the Thai names except for the specks that have only Urak Lawoi names, such as Ko Bulu. Refer to the third map in this article (“former villages”) to see all Urak Lawoi names for all the islands. (Source: We Love Koh Lipe)

Most Thais refer to the Urak Lawoi as Chao Leh, meaning “sea people,” while Malays call them Orang Laut, which carries the same meaning and has been in use since at least the 15th century. Many Westerners use the term “sea gypsies.”

Urak Lawoi, pronounced oraak lo-woy, also means “People of the Sea.” While the above terms are not derogatory, the Urak Lawoi I know prefer the term that they use for themselves. One reason for that is how their tribal name distinguishes them from the Moklen and Moken, two other sea-based tribes in the Thai Andaman that share some similarities with the Urak Lawoi, but are also distinctive from them.

Imagine pulling up to a totally uninhabited Ko Lipe for the first time early last century, knowing that you had arrived at your new forever home.

Original inhabitants

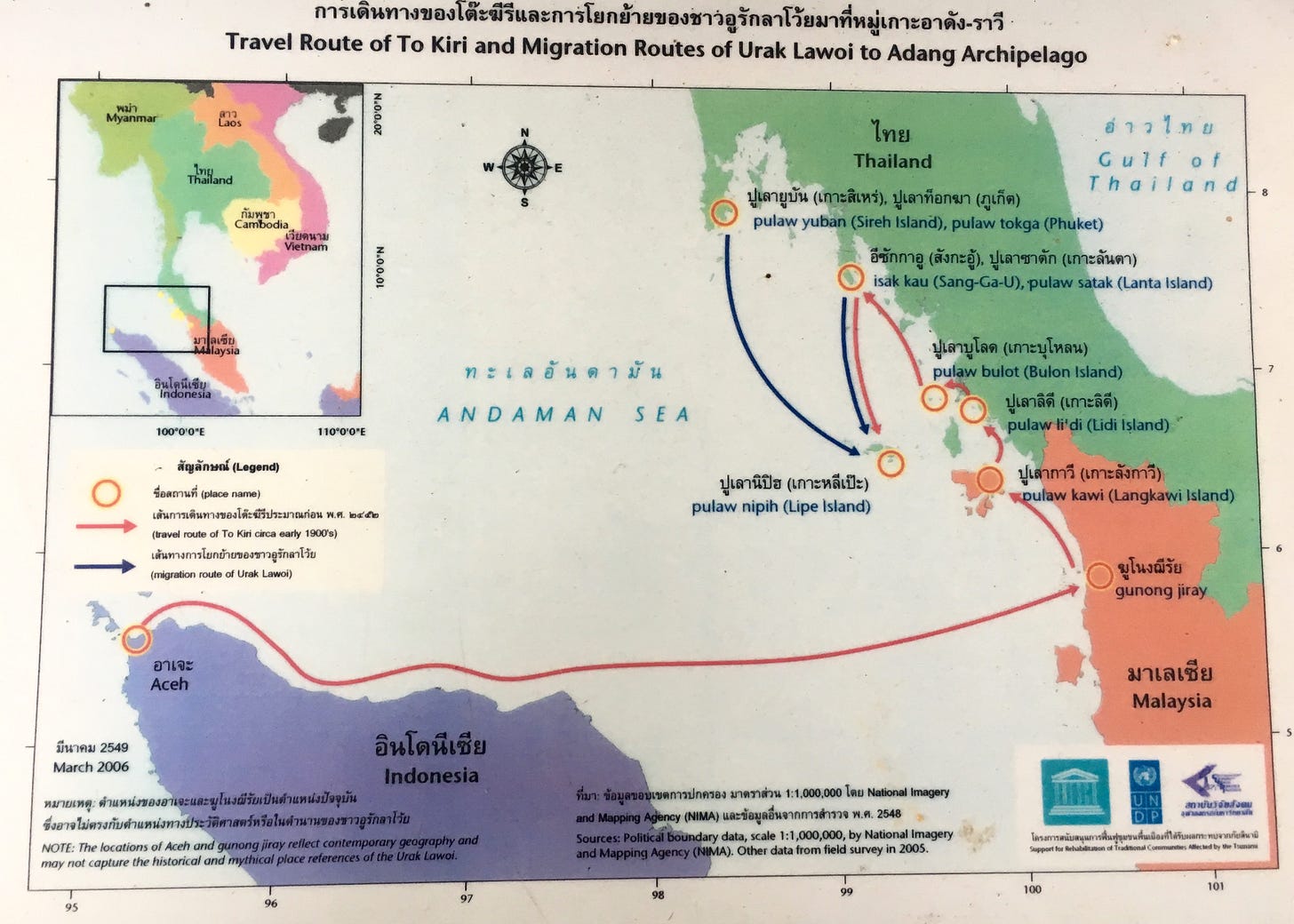

The Urak Lawoi are thought to have first settled in a then uninhabited Butang archipelago around 1910 with help from an explorer, Toh Kiri, who hailed from Aceh in the north of Sumatra.

He spent years sailing up the west coast of the Malay Peninsula before settling on Ko Lanta, considered to be the original home of the Urak Lawoi even if their true origins may trace down to what’s now Kedah state in Malaysia. On Ko Lanta he married an Urak Lawoi woman, Mi-ah, and became a leader of the community.

According to the most widely accepted account, the governor of Satun province, Phraya Poomnardpakdee, invited Toh Kiri and a group of Urak Lawoi to settle in the Butang archipelago. This was advantageous because, at the time, the governor was one of the Siamese leaders negotiating border demarcations with a British Empire that ruled over much of what is now Malaysia. Having mostly lifelong residents of Siam living in the archipelago strengthened the argument that it was part of Siam.

Ultimately King Chulalongkorn was able to keep the Butang archipelago and Ko Tarutao as part of his shrinking empire, handing the islands of Langkawi and Penang to the British along with Kedah and other parts of the Malay Peninsula.

It took Toh Kiri (route in red) several years to reach Ko Lanta Yai. He married twice before moving to Ko Lipe, sadly losing his first wife to disease on Ko Bulon. (Source: The Urak Lawoi’ of the Adang Archipelago)

The reality was probably not so simple, and the idea that Siamese leaders gifted these islands to the Urak Lawoi fits a prevailing nationalist narrative in official accounts of Thai history, which often portray indigenous groups as beneficiaries of generous Thai leaders. The Urak Lawoi and many other tribes in what is now Thailand have a long, albeit murky, history of deliberately evading authorities.

These adept seafarers had for centuries lived semi-nomadically over a large swathe of what’s now the Lower Thai Andaman, with settlements on Phuket, Ko Phi Phi, Ko Jum / Pu, Ko Libong, Ko Ngai, Ko Mook, Ko Bulon and in La-Ngu on the mainland, as well as on Ko Lanta. It’s unlikely that at least some of these Urak Lawoi had not ventured to the Butang archipelago prior to the 1900s.

The mountains of Ko Adang, the largest island in the Butang archipelago at 30 square km, as seen from Ko Tarutao.

The archipelago’s modern Urak Lawoi view Toh Kiri as a protective icon. A spirit shrine with a small wooden image stands in his honor on Ko Lipe, hidden from tourists. His death in 1949, reportedly by snake bite, ended a four-decade era in which the Urak Lawoi had the Butang archipelago almost entirely to themselves.

In those early years they subsisted off a huge variety of marine life, including the once-abundant sea cucumbers, along with jungle plants like sea almond, jackfruit and nitta sprout. They had little notion of money or ownership. While they grew limited crops, their lifestyle was more similar to hunters and gatherers than farmers. It sounds cliche, but the Urak Lawoi lived in harmony with a natural paradise.

Batik sarongs, like these hung out to dry on Ko Lipe, are still the primary form of clothing for many older Urak Lawoi women throughout Southwest Thailand.

Threats from pirates and Taukay

During World War II, hundreds more Urak Lawoi journeyed to the remote archipelago from more populous areas to escape military conscription or forced labor imposed by the Japanese forces that were occupying Thailand. The first commercial fishing trawlers were also spotted around this time.

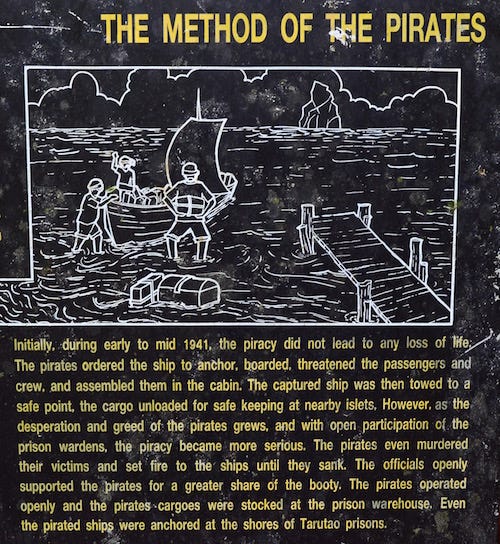

Then came the pirates, mostly former prisoners from a penal colony on nearby Ko Tarutao that was abandoned by Thai authorities during the war. They pillaged ships in the Straits of Malacca, killing many foreign sailors and occasionally chasing their targets into the Butang archipelago. The pirates are not known to have harmed the Urak Lawoi, but they probably caused them some stress.

The pirates of Ko Tarutao sailed through and stopped in the Butang archipelago often during their infamous five-year run of piracy, which was eventually thwarted by the Royal British Navy. (Source: Ao Talo Wao Historical Trail)

Yet the outsiders who impacted the natives most dramatically in the mid-20th century were those known as Taukay, Chinese-Thai men from the mainland who exchanged boats and money for fish, labor and other goods and services from the Urak Lawoi. Ultimately, the Taukay trapped many of the islanders in debt cycles that shattered their old subsistence lifestyle. It was a sign of things to come.

The marine park: friend or enemy?

Five decades ago, the stilted, thatch-walled homes of the Urak Lawoi still dotted many beaches on Ko Lipe, Ko Adang and Ko Rawi. Their permanent villages were joined by dozens of seasonal camps spread around these islands as well as Ko Tong. Even with the presence of the Taukay, the Urak Lawoi’s freedom to fish, forage and slap huts together wherever they pleased was not in question.

That began to change in 1974, when the Thai government laid claim to the whole archipelago by establishing Mu Ko Tarutao Marine National Park. In the eyes of Thai authorities, the Urak Lawoi became encroachers.

Prior to the establishment of the marine park, the Urak Lawoi dwelled in any of the 16 villages and 37 camps shown on this map. Afterwards, they were confined to only a few villages and “strongly discouraged” from camping elsewhere. (Source: The Urak Lawoi’ of the Adang Archipelago)

At first, Thai officials considered displacing the archipelago’s indigenous islanders to the mainland. In the end, though, they resolved to forcibly relocate all of them to Ko Lipe, where the largest Urak Lawoi villages had already been established along with coconut groves and houses built by the Taukay. Over the course of the 1980s, the vast majority of the natives had no choice but to make Ko Lipe home.

Resistance from a few stubborn elders did eventually result in Thai officials allowing two Urak Lawoi villages to stay put at Ao Talo Puya and Ao Talo Cengan on the northeast coast of Ko Adang. Thai authorities granted this right in 1998 on the condition that no new structures would be built. Around 15 bare-bones houses are still found in each of these quiet villages today.

If left to their own devices, the Urak Lawoi would have most likely conserved the archipelago’s natural resources by virtue of their subsistence lifestyle. Instead their sustainable ways put them at a disadvantage, as people who had cleared large tracts of forest to make way for farms on islands like Phuket were rewarded with land rights that turned out to be immensely profitable over the ensuing decades.

Of course, a lot of good did come out of Thailand’s conservationist push during the 1970s and ‘80s. Many islands that might have been heavily developed for tourism remain largely undeveloped as a result of those decisions. But in the Butang archipelago, the conservation came at the expense of the Urak Lawoi. And it did not stop outsiders from reaping the spoils of big-money tourism.

Temporary Urak Lawoi shelters at Patay Panyak, also known as Sunset Beach, on Ko Lipe in 1997. Privately owned resorts and a house for Thai princess Sirindhorn were later built near this beach, which national park authorities have increasingly laid claim to since 2014. (Source: The Urak Lawoi’ of the Adang Archipelago)

Tourism changed everything

A handful of Urak Lawoi families — including some of those descended from Toh Kiri and Mi-ah — did win land rights on Ko Lipe.

The island’s very first “resort” was opened by an Urak Lawoi village headman on Patay Panyak in 1984. It had seven huts and one shared toilet. According to records kept by the owner and later shared with researcher Supin Wongbusarakum, these huts accommodated many of the 184 foreign travelers who visited Ko Lipe per year, on average, between 1982 and 1991.

Exploitation of the Urak Lawoi and their native lands increased as the potential for tourism profit grew. Unscrupulous investors paid a pittance for beachfront properties by convincing islanders that the national park was going to seize all of it anyway. At least this way, their argument went, the Urak Lawoi could get a little something for the land that they had been living on for generations.

Most of the 90% of natives who never received official land rights now live in a cramped village on Ko Lipe. Many are stateless, relying on charities and the generosity of those Urak Lawoi who weren’t left out of the tourism boom for health care.

Some families have unsuccessfully spent large sums of money fighting for land rights in the sluggish Thai court system, which has a tendency to rule against indigenous people. In 1998, the head of one family who built bungalows on his native land was arrested and briefly imprisoned in Satun. After dumping around 500,000 baht ($16,000 USD) into costs related to a legal case, his family finally won rights to build on their own land. To this day, other land rights cases are ongoing.

Property on Ko Lipe, such as this plot being advertised in 2014, fetches high prices for long-term rental. More often than not, the Urak Lawoi are left out of these deals.

Meanwhile, the pace of tourism development quickened in the late 2000s as more than 100 resorts, some of them enormous, covered much of Ko Lipe’s four square km of terrain. Most resorts are owned and operated by outside investors and staffed by mainland Thais and foreigners, including many from Myanmar.

Some of the modern Urak Lawoi work as cooks, cleaners and construction workers, among other jobs, on Ko Lipe. Most of the island’s longtail boat drivers, who provide the skills and knowledge behind lucrative day tours, are Urak Lawoi men. National park staff and other authorities, including the police and Navy personnel stationed on Ko Lipe, are nearly all Thai people from the mainland.

In addition, some Urak Lawoi lament how their native language and traditions are disappearing under the weight of tourism and modernization.

Aimed at cultural assimilation, Thailand’s centralized public education system largely ignores indigenous languages and customs in schools. And some modern Urak Lawoi are more interested in mainstream Thai culture than the ancient wisdom of their people. It is slipping away.

Take a walk through the Urak Lawoi village on Ko Lipe. (Source: chaolehfilm)

Cause for hope

Ko Lipe has plenty of Thai and foreign residents, as well as tourists, who have taken active roles in preserving the Urak Lawoi culture while encouraging the native islanders to take pride in themselves. Awareness campaigns like The Urak Lawoi Project and books like photographer Milos Prelevic’s Molded by the Sea drive home the point that this is a culture worth cherishing.

One tradition that has stuck is Plajak or Loi Rua, to use the Thai name. In this three-day festival held on a full moon during the 11th lunar month, Urak Lawoi gather to float away bad luck on miniature boats made from zalacca wood. On board they place dolls representing a piece of their own spirits, as well as finger nails, handmade candles and fruit for ancestor spirits. The boats are released for the sea to carry away, spiritually cleansing those who take part in the ritual.

It’s true that many Urak Lawoi are now involved in mainstream society, enjoying pre-packaged noodles, watching Thai TV shows and surfing social media on their smartphones. Yet the Plajak ceremony shows the spirit of their sea culture is alive. 🌴

Sources:

- The Urak Lawoi’ of the Adang Archipelago by Supin Wongbusarakum with support from UNESCO and UNDP (2007)

- Urak Lawoi: A Field Study of an Indigenous People in Thailand and their Problems with Rapid Tourist Development by Lotta Granbom with support from Lund University (2005)

- On the Origins of the Urak Lawoi’ by Stephen W. Pattemore and David W. Hogan with support from The Siam Society (1989)

- Men of the Sea: Coastal Tribes of South Thailand’s West Coast by David W. Hogan (1972)