The thrill of an airport floor

How the Thai restaurant community of Burlington, Vermont guided me towards a travel writing career in Thailand.

When it comes to international travel, nothing is like the first time.

It happened for me in 2005, when I was a 25-year-old bartender getting to know some Thai people, as well as Vietnamese and Karen people (of Eastern Burma), and many others from overseas who had settled around Burlington, Vermont.

Some had struggled to reach the United States as refugees from South Vietnam and Laos during the 1980s. Others came during the Obama years via refugee camps in Western Thailand, not far from where the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) still challenges the Burmese military for autonomy in the native Karen lands that straddle the jungle-cloaked Dawna and Tenassarim mountains near Thailand.

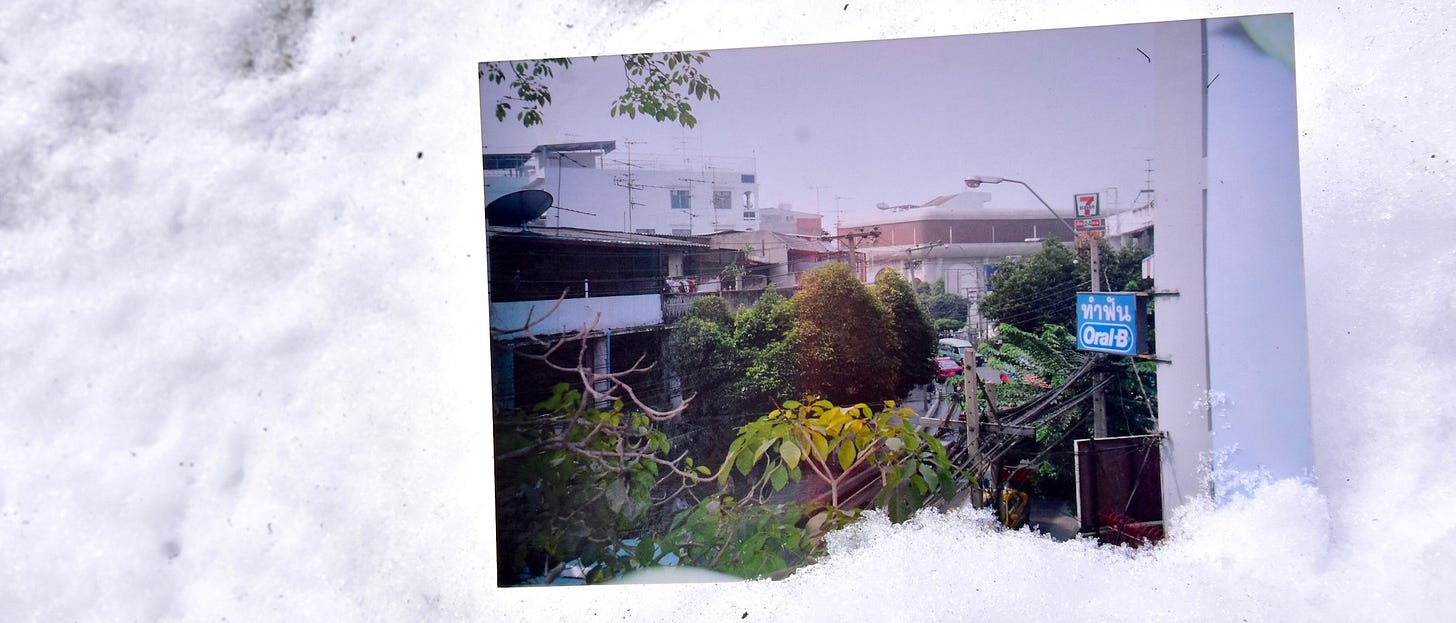

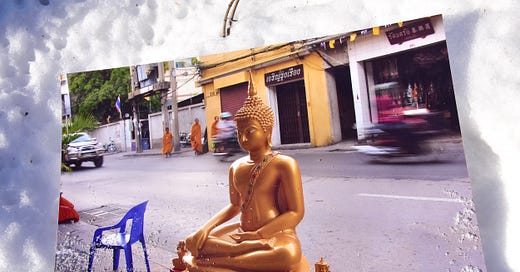

(About the photos: Prints of some images taken 2005-09 were photographed in the snowy western Massachusetts woods, where I grew up, in late January 2022.)

Some of the Thais I knew in Burlington hailed from the shimmering green rice fields of Isaan (the northeast of Thailand); others from the jagged cliffs of Phang Nga and Krabi in the beach-rimmed south or the steep, shrine-dotted mountains of Chiang Mai up north. Many came from Bangkok, be it a glitzy mansion in Kaset Nawamin or a simple flat in a working-class Thonburi neighborhood. Most traveled halfway around the world to work in America.

They included former cruise ship workers, former policemen, former drug dealers, former schoolteachers, former street-cart vendors, and wealthy grad students who’d never worked a day in their lives.

I knew Thai couples and individuals who would wander the cities and towns of the United States until they found good jobs with a reasonable employer in a place they didn’t mind. Then they’d work as much as possible, living frugally until enough money had been saved for a triumphant return to Thailand, or a down payment on a restaurant and/or a home if they decided to stay in the States.

More than a few were drawn by the promise of American wealth, only to find themselves struggling with poverty, magnified by the shame of having family and peers in Thailand who couldn’t believe that anyone might have trouble saving money in America. (Rent for an average apartment in Burlington now stands at around $1,500 per month, while some restaurant staff might make only $500 a week.)

Others thrived. Some reached Burlington after years of restaurant success in Boston or New York — or Bangkok. A few who came from wealthy families used the restaurants merely as social settings as they worked towards a secondary degree or managed their obligations remotely. One friend once asked me to join him in the opening of sushi and cocktail bars in the Virgin Islands. They are all globally minded Thais seeking whatever it is that each of them seeks in America.

They befriended me. Why? At first I think it was because a pair of twenty-something prep cooks, Three and What, enjoyed teaching me Thai curse words. In serious voices they’d say, “Hey Dave, yit bpet means ‘fuck a duck.’” “Yit bpet,” I’d reply. They’d giggle and mumble, “fuck a duck, yit bpet, hahahaha...”

That was the beginning. Yes, the entire course of my life over the ensuing 20 years traces back to laughing about some fucking ducks in a restaurant. Such is life.

I worked at three Thai-owned restaurants between 2003 and ‘11, when I moved to Thailand. For several years I ran the martini bar at Bangkok Bistro, a.k.a. “the Bangkok,” which still exists around the corner from its original spot on Church Street, the bustling pedestrian-only food and shopping street in downtown Burlington. Many Québécois would visit over summer weekends.

I also did lunchtime kitchen and serving work at Tiny Thai, the diminutive BYOB eatery that still thrives in Winooski. A third job, shorter lived than the others, was at Tantra (since closed), where staff members of these and many other restaurants would often meet up for ‘pre-game’ drinks before hitting the bars.

Among the many great Thai friends I made during those years is P’Aoy, my first Thai language teacher and a mentor who I’ve known for two decades; Kata (a.k.a. Bobby), a specialty cocktail wizard and now an accomplished DJ; Tom, who I saw work every shift, lunch and dinner, for months at a time; Champ and Pearl, ambitious restaurateurs; Tong, who was a blur of smoke and fire at the wok on busy nights; Manatat, who fully embraced Vermont; P’Pui, who runs her busy restaurant with fairness and integrity; and T, a ‘big sister’ figure who worked hard with me and others to sell pad Thai, massaman curry and strong cocktails at the rain-soaked Phish festival up in Coventry, Vermont, back in the summer of 2004.

Another friend is Byu Lay, a kind-hearted Karen man whose family’s success in Burlington is a miracle after their dangerous escape through the jungle, followed by a lost decade at a minimally equipped refugee camp in the deep wilderness of Umphang district. Arriving with little preparation in 2007, they were among the 70,000 to 100,000 refugees from Burma — at any given time over the last three decades — who await hope at the remote camps that dot the western Thai borderlands.

(Total refugee entries allowed by the US have declined from nearly 75,000 in 2009 to barely over 20,000 in ‘18 and only 11,400 in ‘21. At the same time, the number of Karen and other groups fleeing Burma has increased as the country continues to destabilize following the Burmese military coup of 2021. Of course, the Karen people of Burma are only one of the many refugee groups around the world who would very much like to bring their energy, creativity and resoluteness to America.)

There was also Tommy, a tall and slender ladies man from Udon Thani who performed all restaurant roles with skillful ease. I never once saw him crack under pressure, be it at the sushi bar or in the kitchen, or behind the bar with me. He spoke little, but was a joy to be around, always managing to keep the mood light no matter how busy and understaffed we happened to be.

Tragically, we lost Tommy last year. He is remembered fondly.

I bought phrasebooks in Thai, as well as Vietnamese and Burmese, and failingly attempted to follow the spoken tones that pin-palled around the restaurants. My tongue increased its spice tolerance in after-shift feasts of dense curries, whole snappers bathed in boiling lime and chili, and so much more. I toasted rice at home so that I could get the cooks to make nam tok muu after work.

In late 2004, T was the one who encouraged me to buy a plane ticket soon before she had been set to fly out to see her family in Nakhon Nayok, located a three-hour drive northeast of Bangkok in the rice- and fish-farming countryside of eastern Thailand. I sloshed around the frigid streets of Burlington to apply for a passport, having never needed one before in my life. At the time, the furthest I’d gone internationally was Montréal up in Canada, a two-hour drive north of Burlington.

My first-ever passport arrived two days before my first-ever international flight. It was with Japan Airlines heading New York (JFK) to Don Mueang (DMK) in Bangkok, with a short layover at Tokyo Narita (NRT), in mid January 2005.

I flew solo. Tea and some of her family members agreed to meet me at the airport when I arrived. This was, of course, long before smartphones, and we had limited faith in the Nokia and Razor “cellies” of that era.

Upon landing in Tokyo, the captain’s voice cracked over the cabin:

There will be a delay. Because, it is a blizzard.

Fat snowflakes billowed past sideways outside. After completing the 14-hour flight from New York, it was another four-hour wait on the runway.

Narita was packed and chaotic — all flights grounded until the next morning, 12 hours away. Queues for hot food stalls stretched for hundreds of meters, so I had seaweed, peanuts and a bottle of sake for dinner. I tried to sleep in a corner of the chilly airport. With the threat of SARS still lingering in Asia, many people wore medical face masks overnight. When morning came, no flights were available.

Twenty-four hours later, I was still stuck in Narita. Turns out that an airline worker strike happened to coincide with a blizzard that day. Such is life.

I sat down on the floor and wrote in my journal:

January 16, 2005, Tokyo Narita Airport:

As the man beside me whispers ‘this is the worst golf trip ever’ to his companion, further delays are announced in muffled Japanese. After 24 hours stranded in this terminal, I ask myself, why am I doing this? Why did I drop everything and spend $1,000 to go halfway around the world from home?

Why? Because this very sense of adventure and unpredictability is what I’ve been searching for. If I end up in Thailand on my own, no big deal. I can always find a hostel, meet some people and see where the wind blows me.

For now, I’m lucky to be here with good people from all over the world. I’ve met a sweet elderly Israeli couple, a cool-headed Australian surgeon, a hilarious businessman from Pakistan, and a college student, John from London, with whom I’ve traversed the airport many times over, riding the trams to the other terminals to have a look around and pass the time.

There is also an orange-robed Buddhist monk from Thailand. Silently meditating on the heating vent throughout this ordeal, his patience is a beacon.

I’ve heard it said that ‘to travel is to endure discomfort of the body in order to gain freedom of the mind.’

Sure, I could have a meltdown like some of my fellow passengers. Instead, I’ll enjoy sharing sake with strangers amidst the great flow of international air travel.

When my flight finally landed at Don Mueang in Bangkok, friends were waiting. I was so tired that all I remember from that night is standing in an elevator, wearing a grey Adidas T-shirt, as someone said, “You look really tired.”

But I’ll never forget the next morning. We took a noisy public khlong boat up the murky San Saeb Canal to Bang Kapi in the working-class eastern reaches of Bangkok, where we bought live fish at a colossal fresh market and gracefully released them into the khlong from a rickety wooden footbridge.

Over the next few weeks in Thailand, how taken I was with the grace, laughter and spirituality of the people I encountered, and the beauty of their country. Wide-eyed I watched bulging flowers and wildlife — monkeys, elephants, big snakes — that I’d never seen while driving a ‘94 Civic with dark-tinted windows to Ayutthaya, Nakhon Nayok, Bang Saen, and back to Bangkok. In that fascinating megacity of some 18 million people, I checked into a 5,000-baht ($150 USD) per-month room in a Din Daeng serviced apartment low-rise, called The Living Room. (It’s still there, accommodating working folks and students at Prachasongkra Soi 25.)

I liked Thailand so much that I returned from February to April 2007, adding side trips to Ko Samui and Siem Reap in Cambodia. That was also when I first met Khao San Road and other classic Bangkok traveler haunts that I’d missed in ‘05.

Soon after the '07 trip, I started actively learning more about Thailand and the rest of Southeast Asia. I closely followed the Yellow Shirt - Red Shirt standoffs, watching in disbelief as the Yellows occupied the Bangkok airports in 2008. I replaced the booze with oolong tea, studied Buddhist scriptures and often stayed up late crafting travel itineraries in preparation for an inevitable return to the East.

In 2008 I became a Travelfish member, relying on that website in ‘09 as a virtual travel guide during a four-month backpacking swing through Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. By late 2011, I had a degree in Southeast Asian Studies and my first paid travel writing gig, updating the Southwest Thai islands for Travelfish. Bobby and Tommy were the last to wish me well when I walked out the door of Bangkok Bistro on my last night of work that October.

Since then, I’ve been extremely fortunate to have traveled a whole lot more, even if the past couple of years have been a bit of a rough ride for many of us. With the threat of Covid still looming, so few people are traveling abroad in early 2022 that arriving at the once-chaotic JFK Airport on a flight from Tokyo recently reminded me of the typically swift and leisurely landings I’ve had at Burlington International (BTV).

But international travel was never meant to be fast or easy.

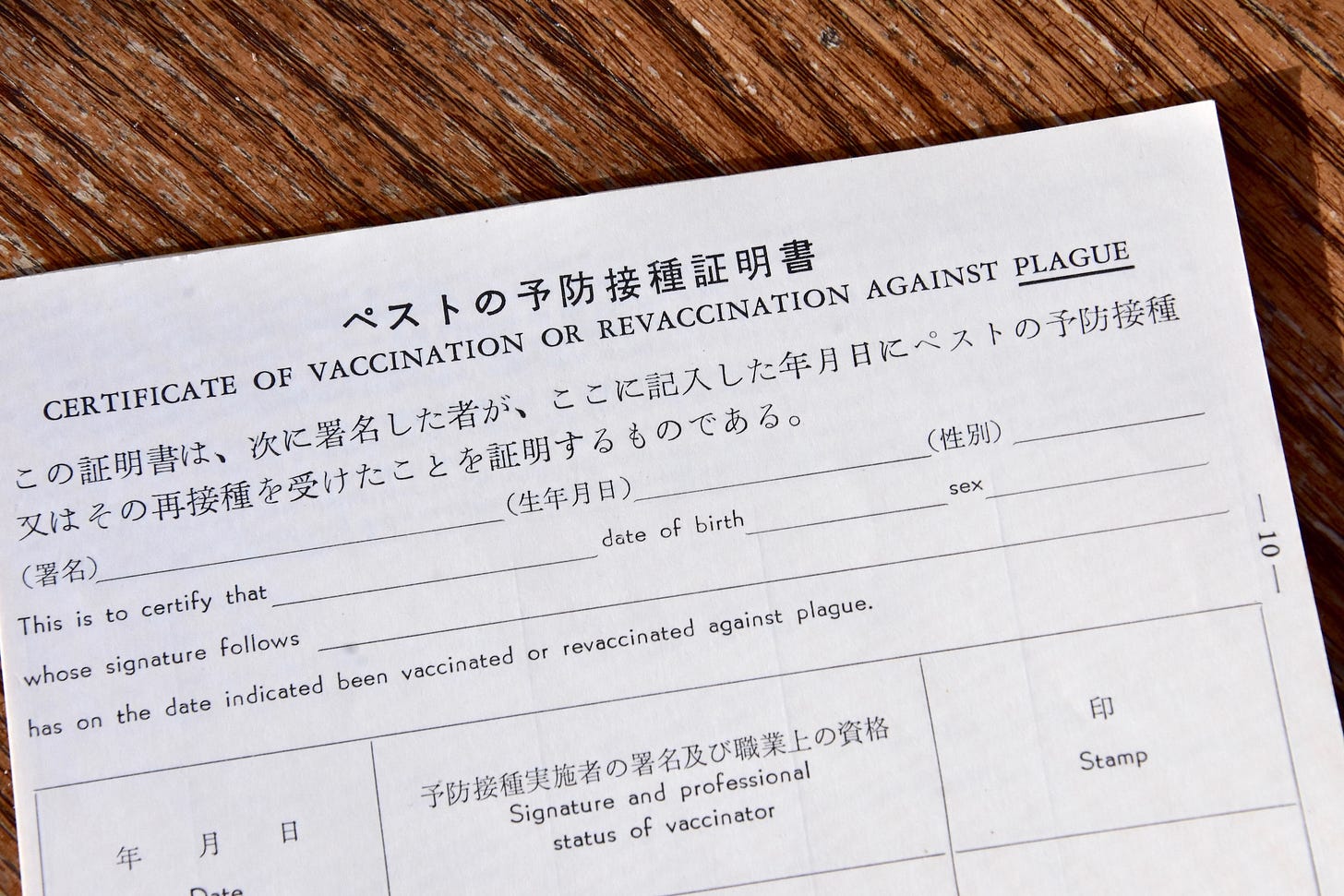

My 99-year-old grandfather recently told me about the passenger ship journeys that he and his family took between Japan and California, first in 1948 and then several times in the ‘50s and ‘60s. They took 14 days, with a one-night stopover in Honolulu. All passengers were required to show proof of various vaccinations, and each was individually screened for illness by public health officials upon arrival at the ports in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

As a 25-year-old in 2005, I was pretty damn keen to leave icy Burlington and visit tropical Thailand with some good friends. Hanging around a Narita airport terminal for 36 hours was nothing compared to the weeks and months that travelers spent at sea, or on hooves and wheels, in the not-so-distant past.

And you know what? Those 14-day sea journeys were nothing compared to the convoluted and often unfair entry processes that Thais need to go through in order to come to America. Nor is that much of anything compared to waiting 10 years in a refugee camp for a chance — any chance — at a better life elsewhere.

Covid is still making international travel more stressful and time consuming than it used to be for many of us. It has also complicated and at times stalled the already complex task of resettling needy refugees in cities like Burlington.

The truth is, though, that the swabs up our noses and the angst in our guts are only the latest entries in the barrage of challenges that travelers have faced right down through the centuries. In the future, many more young people will feel the thrill of their first breaths in a foreign land. 🌴

Thai Island Times by David Luekens is an independent, reader-supported newsletter sharing the beauty, challenges and distinctive identities of Thailand’s islands and coastal areas — and occasional stories from other parts of Thailand and beyond.

Great to see the newsletter this morning. I loved this comment:

A wise person once said, ‘To travel is to endure discomfort of the body in order to gain freedom of the mind.’

Something to remember as we start to travel again!

Cheers,

Dom

Great story, thanks for sharing it David! My first trip was in ‘95 and was a life changing experience. Looking forward to visiting the country for the first time in two years later in February. Yep lots more requirements nowadays and that “angst in the gut” that you’re describing, but doing it anyway…that’s the spirit for me. Thank you!